Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri: does Sam Rockwell deserve awards for playing a racist?

“It seems to me the police department are too busy torturing black folks to solve actual crime,” says Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand) in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. In this darkly funny drama from Martin McDonagh, Mildred Hayes is a grieving mother who hires provocative billboards to pressure the local police department into solving the case of her murdered daughter. Three Billboards is about grief, but with police brutality an ever-present theme, it’s clear that this is also a film with a point to make about racism.

McDormand’s performance captures Mildred’s heartbreak in all its vacillations between crotch-kicking anger and poignant regret. She handles a script of obscenities with stone-cold expertise, while the audience is torn between standing up and cheering, or cringing in solidarity with Mildred’s teenage son (Lucas Hedges). It is McDormand’s co-star, Sam Rockwell, however, who dominates the conversation surrounding this film’s Oscar nominations. Rockwell came under fire after his portrayal of racist police officer Jason Dixon won ‘Best Supporting Actor’ at the Golden Globes.

Multiple characters in Three Billboards insinuate that Officer Dixon is responsible for torturing “black folks”, although he is rarely specifically named as the perpetrator. Officer Dixon is bigoted, violent and cruel, behaving in ways that had me hand-over-mouth in horror at times. It is reprehensible, according to the backlash online, that such a character could lead to an Oscar win for the actor.

Rockwell’s performance is undeniably visceral. His portrayal of Dixon produces incredible extremes of emotion in the audience, not least because he embodies the swaggering ignorance and strength of conviction that reminds us of every white male racist in a position of power we have ever seen.

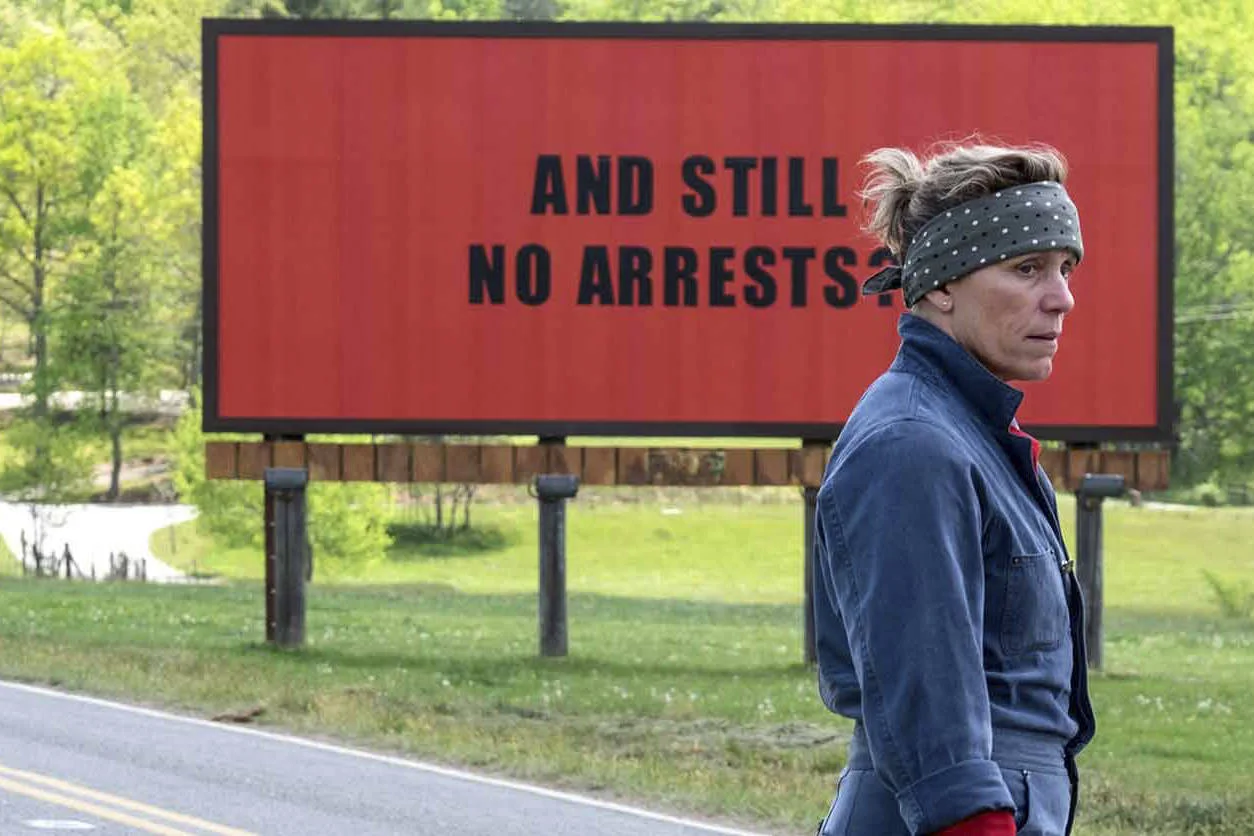

Mildred Hayes (Dormand) squares up to Officer Dixon (Rockwell), Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Misouri

The problem is that Three Billboards asks the audience to feel some degree of pity, if not sympathy, for Dixon, and there is a great deal of comedic value in his character. More than once the audience finds themselves laughing out loud, only to catch themselves, unsure at whose expense they do so.

Dixon lives with his mother, reads comic books at work, and has no real capacity for expressing emotion or reading the obvious contempt others have for him. And yet, contempt is the most dangerous response to have to men like him. His violence is all the more terrible and unpredictable for the way he is infantilised on-screen.

Those who take up issue with Rockwell’s award nominations do so because they believe the character to be redeemed by the film’s conclusion. Martin McDonagh responds, “I don’t think I redeem him, or forgive him, or try to make him a hero because the point is that there are no heroes or villains. The film isn’t about good and bad, left and right. It’s just trying to find the spark of humanity in people – all people.”

It is certainly a script that challenges the natural desire to ‘pick a side’ or identify with one character over the others. While this kind of film-making has the capacity to overturn our preconceptions and be truly moving, there is still plenty of room for criticism in McDonagh’s approach to race in Three Billboards. If you’ve yet to watch Three Billboards, I’ll warn you that the following contains some significant spoilers.

Four black characters occupy crucial elements of the story, though all the starring roles are white. First, the story of the unnamed black male arrested and reportedly tortured by Officer Dixon creates a permanent undertone of racial hatred. This unpunished crime, we assume, is why Jerome (Darrell Britt-Gibson) spits at Dixon at the foot of one of Mildred’s billboards.

Jerome is our second character, whose decision to spit at and behave provocatively towards Dixon sent my eyebrows shooting upwards in disbelief. I’m not sure how much I believe that a young black male, without the protection of a single witness, would risk behaving in such a way towards any police officer, let alone one that is known to be racist and violent. This is either a huge oversight in the script, or a deliberate move to place Jerome in a threatening situation, calling upon the cultural context of racist police brutality to create tension.

The narrative will go on to show the false arrest of Denise, a black female shop-owner, which is orchestrated to threaten Mildred. Soon after, a black Chief of Police will dole out justice just as things seem to be getting out of hand in Ebbing. It’s fairly believable that a police department could go as far as framing a black woman for the possession of marijuana as a means to ‘get at’ those close to her. But then why must the film cheapen this otherwise wry plot development by suggesting that Denise and Jerome start dating? Like a racist grandma, the film cheerfully assumes that two black people not only know each other, but must also be hooking-up.

What’s more, the decision to have a newly appointed black Chief of Police save the day feels patronising. Black people are not here to solve our ‘little racism problem’. The racism that the Chief steps in to rectify could have been addressed by any one of the numbers of white police officers already in a position to do so.

Despite these extremely questionable choices, it is clear to me that McDonagh wants to highlight institutional racism in America, showing us the ways in which black and minority ethnic people go unprotected by systems that white people take for granted. Whether he succeeds is certainly debatable.

The truth is, if we want films that go beyond the clumsy attempts of white script-writers and directors to tell black stories, we need to work harder to overhaul Hollywood as one of those institutions in which racism is still all too prevalent. When diversity is permitted to penetrate the hallowed inner circles of film and television, then we’ll find that the stories of marginalised people are being told more accurately.

There are some staggering performances to be seen in Three Billboards, doing justice to a script that is touching, horrifying and hilarious. I certainly don’t agree that Sam Rockwell’s performance should go unrecognised, nor did I personally feel that nominating this film for awards in any way redeems the abhorrent racism it depicts on screen. We must trust, as an audience, that being moved by the stories of people who do bad does not condone bad behaviour. Humanity is complicated, and to have art that reflects that complexity brings us closer to empathy with all people.

Title image of Frances McDormand as Mildred Hayes, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri